NEW YORK—(April 10, 2009) Jill Holtermann Bowers with her cousin Billy (center) and her father Cliff display an old bakery delivery tray and hat in the inner section of the 131 year old family owned bakery.

NEW YORK—(April 10, 2009) Jill Holtermann Bowers with her cousin Billy (center) and her father Cliff display an old bakery delivery tray and hat in the inner section of the 131 year old family owned bakery.NEW YORK--(April, 2009) Holtermann’s neighborhood has undergone quite a few changes over the last century.

Where Claus Holtermann once picked blueberries and peaches to make fresh pies, is now a golf course. A dirt road once traveled by horses and wagons and later his mini orange delivery trucks is now a busy street overrun with speeding SUVs. A bed of two family homes and shopping plazas that boast supermarkets and Dunkin Donuts line the roadway instead of a forest of trees and bushes.

Yet, his bakery nestled around the bend at 405 Arthur Kill Road still stands and remains a staple on Staten Island.

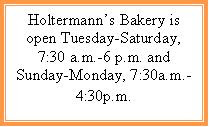

Holtermann’s Bakery has been dishing out fresh rolls, moist crumb cakes and honey cookies since 1878 when Claus Holtermann emigrated from Hanover, Germany and opened his shop in Richmond Town. His descendants later moved it in the 1930s to its current location a few blocks away.

The scenery may have changed and the building’s bricks may have faded over the last 131 years, but that’s about it. The signature white box still bears the cerulean blue lettering. Four generations later, the Holtermann family still works behind the counter and in the kitchen and customers still pack inside to buy their baked goods. Island bakers, like the Cake Chef’s James Carrozza, even shop there for items not produced in their own bakeries.

“He makes a really good sourdough bread. It’s in a small round loaf and has that perfect sour tang to it,” said Carrozza.

The German bakery, on an Island dominated by Italian bakeries, continues to thrive despite a declining economy and an increasingly health savvy climate.

“I don’t know if my ancestors would have imagined it’d still be here with us,” current owner Billy Holtermann said about the longevity of the oldest family bakery on Staten Island.

His eyes darted to a display of Easter cakes shaped like lambs, one slanted off to the side. He delicately moved it back in place.

“People have different ideas of how things should run. So it’s about getting everyone to compromise,” said Billy, 58.

The telephone continuously rings for orders while the bells on the door chime every time a customer opens it. Shelves of boxed cookies and cakes line the walls of the modest, dimly lit rectangular shaped bakery. Jill Holtermann Bowers, Billy’s cousin and assistant manager, works the counter and seems to know everyone who enters by name. She steps out from behind the glass showcase of gooey cinnamon buns and chocolate dipped Easter bunny cupcakes complete with marshmallow tails to help a customer count the number of cookies in a tray.

“I know, I packed them,” says Jill who started packing cookies in the second grade when her grandparents gave her class a tour of the bakery.

“When the tray came to you, you put the cookies in the box. My grandfather said we could have one when we were done,” she said. “Everyone has a different road they can go with this [running the bakery]. I like to get the community involved and bring the Girl Scouts in to teach them about it.”

Her father Cliff has been working there for more than 55 years. Donning a white apron and t-shirt, he helps out in the expansive factory like kitchen in the back where the scent of baking bread permeates the air. Long, wooden flour-coated tables and big mixers that help create the racks of fluffy muffins are scattered about the cement floor. Some of the machines look weathered, like the proof box, which gets the bread to rise just right in a temperature controlled environment. Cliff hopes the bakery will remain in the family.

“That’s why I’m still here. My father worked so hard to build it. It’s like a dynasty,” he said.

The bakery is just as much a tradition for customers.

Elaina Giarratano said she has been enjoying Holtermann’s breads and pastries since she was a child and continued to shop there for her son. Now a Marine and grown himself, he still enjoys their rolls, she said.

“His friends’ birthdays are in August and always landed during the weeks it [the bakery] was closed for vacation. So they always got jipped out of a Holtermann’s birthday cake when they were young,” she added.

Linda Baran, president of the Staten Island Chamber of Commerce and lifelong Staten Islander, attributes the bakery’s success to the family’s work ethic and ability to adapt.

“They’re a dedicated family,” said Baran. “I think they’ve probably remained because they changed their business model with the times,” she said referring to the family’s decision to stop the truck deliveries to homes.

“They did what they could handle. At a certain point they really increased capacity and became a huge operation. I think it took a hard look at things to pull back,” she said in a telephone interview.

Giarratano remembers the orange truck that delivered fresh white and rye breads to her home when she was a little girl.

“I can just visualize it,” she said clutching a bag of rolls she bought for her sister visiting from Maryland. “It was the fifties so my parents ordered a lot of white bread.”

Even though it’s good to market your business and change things around, Baran thinks Holtermann’s has a solid market.

“They have remained conscious of the consumer and how much they pay,” said Baran. “Honestly, I don’t think they need to change anything. They’ve got a great clientele.”

Even with the country in a state of economic decline, the Holtermann family isn’t too worried. Cliff is quick to point out how the bakery survived the Great Depression.

“We haven’t been hurting,” said Billy. “In fact, bread sales seemed to have picked up.”

According to Baran, bakeries might be in a better position than other types of food businesses because as more people decide to eat at home, they may shop for more of their goods.

The increased emphasis on health consciousness could prove difficult though for the bakery relying on decades old recipes. New York City bakeries and restaurants are no longer allowed to cook with trans fats, which raise bad cholesterol and lower good cholesterol, after the city’s board of health voted to ban them in 2008.

“It’s been a pain in the neck. Certain cookies just don’t bake the same and some icings are not as nice as they used to be,” said Billy, shaking his head.

According to James Carrozza, owner of the Cake Chef bakery and the Cookie Jar on Staten Island’s North Shore, the ban poses a problem because it leads to more expensive and less suitable substitutes.

“The companies that manufactured shortenings like Crisco didn’t come up with a good enough replacement. New and approved shortenings don’t work well in baker’s formulas. We were a bakery that always used a lot of butter so it didn’t pose too much of a problem for us, but for the old fashioned type bakeries it did,” said Carrozza.

Marion Nestle, a nutrition professor at New York University, said bakers have to learn to adapt and use other oils, butter, or fats that are not partially hydrogenated. She acknowledged that it could be more expensive.

“The ban was an excellent idea. They [trans fats] are demonstrably harmful to health and the whole point was to take care of the problem without asking individuals to do anything special,” she said in an email.

The ban hasn’t affected long standing customers’ sweet tooth, especially the “Sunday morning crew,” affectionately named by the Holtermann’s staff.

Mike Castellano parks his navy blue Honda right under the blue and white awning every Sunday at 7 a.m. The 79-year-old’s first name is etched on the ground in blue chalk, the “Mi” faded from the rain, to show his “spot” first in line. He puffs on what’s left of his cigar before throwing it aside and paces back and forth with his hands in his pockets near the door in the cold.

According to Castellano, he’s been lining up outside Holtermann’s door for more than 20 years, “Cuz it’s good. They got the best crumb buns around.” He’s even double wrapped and express mailed them to his aunt in Florida.

The moment a hand reaches from behind the curtain to turn the sign to “Open,” Castellano, along with the dozen others who follow a similar routine, shuffle inside. Welcomed by a layered aroma of onion rye bread, sweet pastries and cinnamon, they all seem to know exactly what they want.

Ethel Holtermann, Jill’s mother, thinks the bakery’s connection to the community has kept it going.

“It’s really a neighborhood bakery. That’s why it seems to work so well,” she said.

Where Claus Holtermann once picked blueberries and peaches to make fresh pies, is now a golf course. A dirt road once traveled by horses and wagons and later his mini orange delivery trucks is now a busy street overrun with speeding SUVs. A bed of two family homes and shopping plazas that boast supermarkets and Dunkin Donuts line the roadway instead of a forest of trees and bushes.

Yet, his bakery nestled around the bend at 405 Arthur Kill Road still stands and remains a staple on Staten Island.

Holtermann’s Bakery has been dishing out fresh rolls, moist crumb cakes and honey cookies since 1878 when Claus Holtermann emigrated from Hanover, Germany and opened his shop in Richmond Town. His descendants later moved it in the 1930s to its current location a few blocks away.

The scenery may have changed and the building’s bricks may have faded over the last 131 years, but that’s about it. The signature white box still bears the cerulean blue lettering. Four generations later, the Holtermann family still works behind the counter and in the kitchen and customers still pack inside to buy their baked goods. Island bakers, like the Cake Chef’s James Carrozza, even shop there for items not produced in their own bakeries.

“He makes a really good sourdough bread. It’s in a small round loaf and has that perfect sour tang to it,” said Carrozza.

The German bakery, on an Island dominated by Italian bakeries, continues to thrive despite a declining economy and an increasingly health savvy climate.

“I don’t know if my ancestors would have imagined it’d still be here with us,” current owner Billy Holtermann said about the longevity of the oldest family bakery on Staten Island.

His eyes darted to a display of Easter cakes shaped like lambs, one slanted off to the side. He delicately moved it back in place.

“People have different ideas of how things should run. So it’s about getting everyone to compromise,” said Billy, 58.

The telephone continuously rings for orders while the bells on the door chime every time a customer opens it. Shelves of boxed cookies and cakes line the walls of the modest, dimly lit rectangular shaped bakery. Jill Holtermann Bowers, Billy’s cousin and assistant manager, works the counter and seems to know everyone who enters by name. She steps out from behind the glass showcase of gooey cinnamon buns and chocolate dipped Easter bunny cupcakes complete with marshmallow tails to help a customer count the number of cookies in a tray.

“I know, I packed them,” says Jill who started packing cookies in the second grade when her grandparents gave her class a tour of the bakery.

“When the tray came to you, you put the cookies in the box. My grandfather said we could have one when we were done,” she said. “Everyone has a different road they can go with this [running the bakery]. I like to get the community involved and bring the Girl Scouts in to teach them about it.”

Her father Cliff has been working there for more than 55 years. Donning a white apron and t-shirt, he helps out in the expansive factory like kitchen in the back where the scent of baking bread permeates the air. Long, wooden flour-coated tables and big mixers that help create the racks of fluffy muffins are scattered about the cement floor. Some of the machines look weathered, like the proof box, which gets the bread to rise just right in a temperature controlled environment. Cliff hopes the bakery will remain in the family.

“That’s why I’m still here. My father worked so hard to build it. It’s like a dynasty,” he said.

The bakery is just as much a tradition for customers.

Elaina Giarratano said she has been enjoying Holtermann’s breads and pastries since she was a child and continued to shop there for her son. Now a Marine and grown himself, he still enjoys their rolls, she said.

“His friends’ birthdays are in August and always landed during the weeks it [the bakery] was closed for vacation. So they always got jipped out of a Holtermann’s birthday cake when they were young,” she added.

Linda Baran, president of the Staten Island Chamber of Commerce and lifelong Staten Islander, attributes the bakery’s success to the family’s work ethic and ability to adapt.

“They’re a dedicated family,” said Baran. “I think they’ve probably remained because they changed their business model with the times,” she said referring to the family’s decision to stop the truck deliveries to homes.

“They did what they could handle. At a certain point they really increased capacity and became a huge operation. I think it took a hard look at things to pull back,” she said in a telephone interview.

Giarratano remembers the orange truck that delivered fresh white and rye breads to her home when she was a little girl.

“I can just visualize it,” she said clutching a bag of rolls she bought for her sister visiting from Maryland. “It was the fifties so my parents ordered a lot of white bread.”

Even though it’s good to market your business and change things around, Baran thinks Holtermann’s has a solid market.

“They have remained conscious of the consumer and how much they pay,” said Baran. “Honestly, I don’t think they need to change anything. They’ve got a great clientele.”

Even with the country in a state of economic decline, the Holtermann family isn’t too worried. Cliff is quick to point out how the bakery survived the Great Depression.

“We haven’t been hurting,” said Billy. “In fact, bread sales seemed to have picked up.”

According to Baran, bakeries might be in a better position than other types of food businesses because as more people decide to eat at home, they may shop for more of their goods.

The increased emphasis on health consciousness could prove difficult though for the bakery relying on decades old recipes. New York City bakeries and restaurants are no longer allowed to cook with trans fats, which raise bad cholesterol and lower good cholesterol, after the city’s board of health voted to ban them in 2008.

“It’s been a pain in the neck. Certain cookies just don’t bake the same and some icings are not as nice as they used to be,” said Billy, shaking his head.

According to James Carrozza, owner of the Cake Chef bakery and the Cookie Jar on Staten Island’s North Shore, the ban poses a problem because it leads to more expensive and less suitable substitutes.

“The companies that manufactured shortenings like Crisco didn’t come up with a good enough replacement. New and approved shortenings don’t work well in baker’s formulas. We were a bakery that always used a lot of butter so it didn’t pose too much of a problem for us, but for the old fashioned type bakeries it did,” said Carrozza.

Marion Nestle, a nutrition professor at New York University, said bakers have to learn to adapt and use other oils, butter, or fats that are not partially hydrogenated. She acknowledged that it could be more expensive.

“The ban was an excellent idea. They [trans fats] are demonstrably harmful to health and the whole point was to take care of the problem without asking individuals to do anything special,” she said in an email.

The ban hasn’t affected long standing customers’ sweet tooth, especially the “Sunday morning crew,” affectionately named by the Holtermann’s staff.

Mike Castellano parks his navy blue Honda right under the blue and white awning every Sunday at 7 a.m. The 79-year-old’s first name is etched on the ground in blue chalk, the “Mi” faded from the rain, to show his “spot” first in line. He puffs on what’s left of his cigar before throwing it aside and paces back and forth with his hands in his pockets near the door in the cold.

According to Castellano, he’s been lining up outside Holtermann’s door for more than 20 years, “Cuz it’s good. They got the best crumb buns around.” He’s even double wrapped and express mailed them to his aunt in Florida.

The moment a hand reaches from behind the curtain to turn the sign to “Open,” Castellano, along with the dozen others who follow a similar routine, shuffle inside. Welcomed by a layered aroma of onion rye bread, sweet pastries and cinnamon, they all seem to know exactly what they want.

Ethel Holtermann, Jill’s mother, thinks the bakery’s connection to the community has kept it going.

“It’s really a neighborhood bakery. That’s why it seems to work so well,” she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment